Article

Financial Beat

Author(s):

Credit Cards, E-Commerce, Mutual Funds, Retirement, Stocks

Financial Beat

By Yvonne Chilik Wollenberg

Credit Cards

No more liability for unauthorized charges

It used to be that if someone snagged your credit card number, you had two business days after discovery to report the theft. Your liability for unauthorized charges wouldn't exceed $50.

But since it's not easy to notice those charges when the theft is online (you might not realize you've been bilked until you get the next monthly bill), MasterCard and Visa have switched to a zero-liability policy. Now you'll owe nothing if your card or number is stolen, no matter how long it takes you to report it.

The policy applies only to cards issued by US banks. MasterCard requires that your account be in good standing, that you took reasonable care to guard the card, and that you have not reported two or more instances of theft in the past 12 months.

Discover Card also has a fraud-protection policy. It frees you of liability for unauthorized charges when using its card online.

E-Commerce

Electronic signatures will let you do more online

So far, online shopping for loans, cars, and other big-ticket items has amounted to little more than window shopping. You can get price quotes, loan rates, and other information, but completing a deal means downloading an application, signing the paper document, and mailing it. Soon, however, you'll be able to close a mortgage, buy a car, or sign a business deal without pen, paper, or overnight mail. The Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act, which takes effect Oct. 1, gives electronic signatures the same legal status as handwritten ones.

A digital signature isn't a signature at all. It's simply an electronic guarantee that you are who you claim to be when doing business on the Net. Here's how it works: Some personal information is collected from you when you identify yourself in an online agreement. That information is compared with records available from another party, such as a company that verifies credit card transactions or maintains consumer credit histories. If the information checks out, your online identityyour signatureis confirmed.

Consumers Union recommends a few precautions for users of electronic signatures:

- Print out and keep all electronic documents.

- Notify businesses anytime you change your e-mail address, or switch to new hardware or software that might interfere with an e-mail account.

- Close any unused e-mail accounts to avoid lost documents.

The new national standards are expected to boost online retail sales, estimated at $5.3 billion for the first quarter of the year by the Department of Commerce, and hurt the document-delivery business of such companies as UPS and FedEx. With an eye to the future, UPS got into the e-signatures business in 1998 and remains positioned to take advantage of the technology.

Mutual Funds

Be careful: We've entered the age of the outside adviser

Who runs your mutual fund? Before you answer, consider this: Not all funds are managed by the company that sells them. For years, a few firms occasionally farmed out that responsibility to so-called subadvisers. Lately, however, the practice has moved from the fringe of the mutual fund industry to the mainstream.

The Vanguard Group, for example, hires subadvisers to manage all but its aggressive growth fund. Fidelity Investments, known for its own active management, uses subadvisers for its index funds. And while Janus manages its own funds, it is itself a subadviser to other fund familieswith $47 billion of other funds' assets under its control. More than 700 funds (nearly one in nine) are under subadvisory management today, according to Boston-based Financial Research, and the trend continues to accelerate. Outside management is most common with international and global funds, where one in five is run by a subadviser, FRC says.

This can be a good deal for investors. A subadviser is often less expensive to the fund company than an in-house manager, helping keep investor costs down. And he's usually an expert in the field his fund focuses onunlike some company managers who, say, get pulled from the family's large-cap fund and put in charge of emerging markets.

Problems for investors can arise, however, when a fund company changes its subadviser. For instance, you may not agree with the new adviser's investment style, warns Geoff Bobroff, an industry consultant in East Greenwich, RI. You may have bought a fund because of its conservative-growth approach, then find that it has turned aggressive because the replacement adviser prefers that strategy.

Although funds must notify investors when they replace a subadviser, shareholders have no say in who is selected. "Your only proxy is with your feet," Bobroff says. "If a fund is subadvised, buy it with caution and re-evaluate whenever the manager is replaced."

Retirement

Why have variable annuities become so popular?

Concerned about the way variable annuities are marketed, the Securities and Exchange Commission has issued an investor alert outlining their pitfalls. Variable annuities, which combine mutual funds and insurance, offer death benefits, tax-deferred earnings, and lifelong payments. They've recently become a popular way to save for retirement, with sales exceeding $120 billion last year.

But SEC spokesman John Heine says that many investors aren't made aware that these retirement accounts are often loaded with high fees and limited benefits. The commission is worried that investors are grabbing up variable annuities without understanding the significant charges they carry.

The alert warns investors to expect surrender charges if they withdraw funds within a specified surrender period, usually six to eight years, plus several annual tolls for administrative costs, mortality and expense risk, and any fees charged by the underlying mutual funds. Any bonuses and special features, such as "stepped-up" death benefits, also generally come with higher fees that may outweigh the benefits.

Investors looking for tax-deferred growth would be better off maxing out their contributions to IRAs and 401(k) plans, says the SEC. There's no additional tax benefit to investing in a variable annuity through your IRA or 401(k), since investment gains are tax-deferred in all three. When you do withdraw money from the variable annuity, it will be taxed at ordinary-income rates rather than at the capital gains rate. And in most cases, a variable annuity's tax deferral benefits will outweigh its costs only if it's held long term.

The investor alert is posted at the SEC's Web site, www.sec.gov/consumer/varannty.htm.

Stocks

What's not to like about online trading? Let us count the complaints

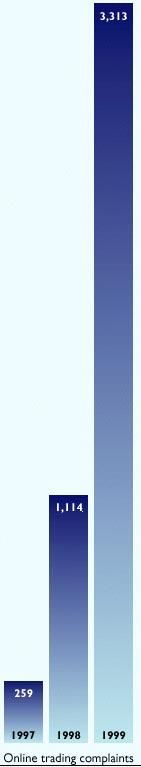

If you've been annoyed by online stock trades that aren't as quick and easy as advertised, you're not alone. Disgruntled e-traders registered more than 3,300 complaints in the 12 months ended in September 1999, a 197 percent increase over 1998 and nearly 2,000 percent higher than 1997, according to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The biggest beef last year concerned online brokers who take too long to execute a trade, or fail to process it at all. Despite industry promises of instant action when you click "send," trades can take hours to complete, some investors complain. The second most common gripe was that Web sites were frequently inaccessible, and brokers could not be easily reached by e-mail or phone. Investors also complained that online brokers botch stock orders and often fail to get the best prices.

If you have a problem with an online broker, your best bet is to write a letter to the firmon paper, sent through regular mailwith supporting evidence such as dates, times, and dollar amounts. You should also file an online complaint with the National Association of Securities Dealers at www.nasdr.com. Contact your state securities regulator as well. You can find a list of state regulators at the North American Securities Administrators Association's Web site (www.nasaa.org).

E-traders opened more than 10 million online accounts by the end of 1999, and the SEC predicts online brokerage assets will reach $3 trillion by 2003.

The author is a freelance writer in Teaneck, NJ.

Yvonne Wollenberg. Financial Beat. Medical Economics 2000;15:16.