Article

Invest in the euro? Maybe

You don't want to hoard the new currency under your mattress, but there are good investments linked to it.

Invest in the euro? Maybe

You don't want to hoard the new currency under your mattress, but there are good investments linked to it.

By Dennis Murray

Senior Editor

Before the euro was introduced a few years ago, there was a lot of talk about how the new currency would break down trade barriers, enabling European countries to gain efficiencies and economies of scale and more easily compete with one another. All of this would translate into stronger profits and better returns for shareholders of European companies.

It hasn't happened yet. The typical mutual fund that invests in European companies lost 21 percent in 2001 and 25 percent so far this year.* Some people are convinced that the euro is partly to blame for that poor performance. In the United Kingdom, which along with Denmark and Sweden hasn't yet adopted the euro, opposition forces are growing. Rupert Murdoch recently spoke out against the euro and will likely use his media empire to create negative public sentiment toward it.

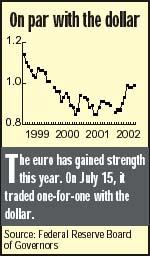

Murdoch, however, is up against 12 countries that have already adopted the euro as their currency. Moreover, this year the euro has been gaining ground against the dollar. On July 15, the two currencies were equal in value, the first time that has happened since February 2000. Experts disagree on how much of the euro's strength results from a weaker dollar, which has reflected the corporate scandals and sluggish stock market in the US.

Regardless of who's right, trying to predict the euro's movements against the dollar is a dicey proposition. Targeting your investments to these fluctuations is more challenging still. True, you could make money by trading eurosholding them for short periods and flipping them for quick profits. But that's easier said than done. "Most of the foreign-stock money managers I deal with don't try to time currency movements," says Emily Hall, a mutual fund analyst with Morningstar. "They find it much too difficult. Individual investors would be better served by making sure their assets are well-diversified," she says.

Chances are you already own investments whose returns are influenced to some degree by the euro: shares of multinational companies like Coca-Cola, DaimlerChrysler, Nokia, and Sony, or of international and global mutual funds, which generally hold a sizable portion of European stocks.

If you don't own much foreign stock, or you simply want your fortunes tied a little more closely to European companies, buy shares of a European mutual fund. Two that Morningstar currently recommends are Mutual European FundClass A and Vanguard European Stock Index Fund.

Vanguard European Stock Index, which tracks the large-company MSCI Europe Index, is the cheaper and less volatile of the two. You won't pay a commission, and expenses run just 0.3 percent of assets. The $4 billion fund's 10-year average annualized return is a healthy 6.5 percent. It isn't very nimble, though, and has few mid- and small-cap stocks. Therefore, when investors flee European blue chips, as they have lately, Vanguard European Stock Index suffers. It's down more than 28 percent this year.

Mutual EuropeanClass A owns predominantly midsized companies, but also some small-caps, and bonds issued by distressed companies. The fund managers specialize in finding undervalued investments, and their strategies have rewarded investors handsomely in the fund's short history: Mutual European, which began trading in 1996, has a five-year average annualized return of almost 8 percent a year. Unfortunately, it charges a 5.75 percent front-end load on initial investment amounts. That's a tough pill to swallow, but if you're patient and hold the fund for a minimum of three years, chances are you'll be rewarded.

*Unless otherwise noted, all performance figures are through Oct. 8.

Dennis Murray. Invest in the euro? Maybe. Medical Economics 2002;21:91.