Policy

Latest News

Latest Videos

Shorts

Podcasts

CME Content

More News

Congress approves a Medicare telehealth extension, community health center spending and more, ending the partial shutdown.

An Oregon Health & Science University analysis of five specialties across all states highlights "ghost" physicians, high-volume core participants and growing worries about access, especially in psychiatry.

Patients are paying more for health care. But what does that mean for your practice?

A conversation with Greg Grant, COO, Specialdocs Consultants.

A majority of states and Washington, D.C., are following pediatric groups and/or prior or state recommendations instead of new federal childhood vaccine guidance.

Pharma, MedTech and diagnostics still operate in separate lanes even as precision medicine, value-based care and outcome-focused models demand integrated systems of care.

Noncompete opponents seeking nationwide regulation should take their arguments to Congress, FTC chief says.

FTC hears from physicians, other professionals about restrictions when workers leave or change jobs.

Innovaccer's 2026 “State of Revenue Lifecycle in Healthcare” report shows most organizations now run AI in live workflows, yet fragmented data and point solutions are slowing scale.

Advance notice projects 0.09% average increase as agency moves to tighten risk adjustment; insurer stocks drop.

The president of the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine describes state of osteopathic medical education.

Medical groups say stepped-up operations by federal agents are stoking fear, keeping patients from hospitals and raising safety concerns for clinicians.

FTC begins new discussion on noncompete agreements in work contracts across health care and the general economy.

New white paper argues pharmacy benefit managers’ slim margins reflect bookkeeping and consolidation, not necessarily low profits, as oversight push intensifies.

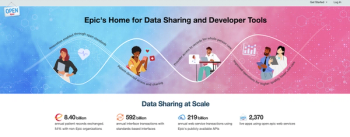

The electronic health records software giant filed its legal response and will seek dismissal of the lawsuit by the Texas Attorney General’s Office.

Texas 2036 aims at health insurance needs in a state where residents have struggled with it.

Johns Hopkins analysts weigh in on national debate on health insurance and ways to pay for medical care.

How an organization in the Lone Star State aims to make health insurance affordable while promoting market competition.

New Medicare payment model aims to take down wasteful spending, but Congress and analysts point out potential problems.

An advocate discusses how ACOs raised red flags about Medicare spending for skin substitute treatments for patient wounds.

What you need to know about the biggest trends that will impact health care in 2026

Progressive Policy Institute finds hospital and corporate ownership of practices climbed to 59% by 2023, whereas independent practices declined fastest in rural communities, and prices rose following acquisitions.

How an organization in the Lone Star State aims to make health insurance affordable while promoting market competition.

How an organization in the Lone Star State aims to make health insurance affordable while promoting market competition.

An advocate discusses how ACOs raised red flags about Medicare spending for skin substitute treatments for patient wounds.